The Castle never ceases to astonish its visitors with strange wonders. Just when you believe you’ve grasped its architecture and mapped its inner workings, it confounds you with a hall or passageway that unravels the careful plans you’ve drawn through your long explorations. Here, nothing is fixed. Everything you think you know is called into question. You find yourself constantly reassessing, not only trying to understand where you are, but also—perhaps more importantly—why you are there. And, truthfully, this process rarely offers a single answer. That, I suspect, is why I return to this ominous, enchanted place again and again. There are too many riddles wrapped in velvet shadows, too many mysteries that refuse to let go. You cannot look away once the Castle has looked into you.

But those are thoughts for another time. Tonight is not the hour to speak of the darker phantoms that haunt my mind. They do not like to be named in moonlight; to write of them now would be to conjure them. And I fear they may not leave.

Instead, let me tell you about one particular room—a room that changed the way I see the Five of Coins.

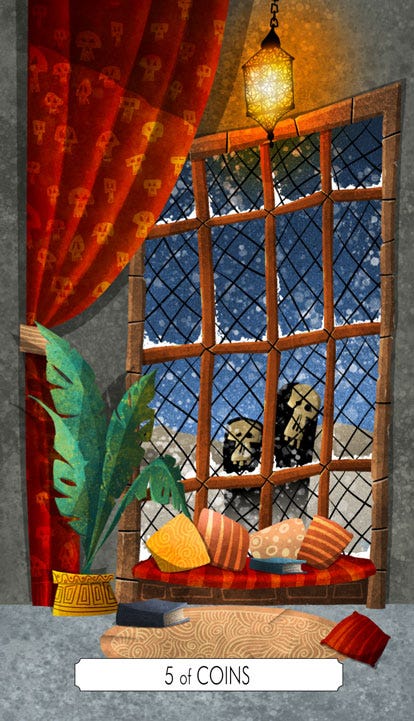

It was after a long day of wandering, my journal inked with symbols, mottos, sketches of friezes and curious sigils carved in stone. Exhausted, I stumbled upon what appeared to be a drawing room. The tall eastern windows were adorned with plush velvet cushions. Books lay open in gentle disarray, as if the reader had left suddenly, fully intending to return. The eerie feeling of abandonment clung to the air. A striped cushion lay abandoned on the carpet like a forgotten thought. A great lantern glowed warmly above me, casting a golden light that soothed, but did not dispel, the unease that clung to the room.

Behind a large, leafy plant, a curtain of heavy red velvet—like something from a theatre—hung pinned back with gold-threaded lace. Intricately embroidered skulls in yellow-gold thread grinned ominously. But it was the scene outside the window that truly froze my breath.

A snowstorm howled beyond the glass, white drifts glowing under the dim light. The wind rattled the windowpanes, whispering of forgotten worlds. And then—out of the swirling white—two ghostly figures emerged. They moved slowly, weighed down by suffering. Hollow eyes locked with mine. Their faces were carved with sorrow, as if time itself had left scars in their bones.

I stepped back, heart racing. But then I realised—

I was inside the Five of Coins.

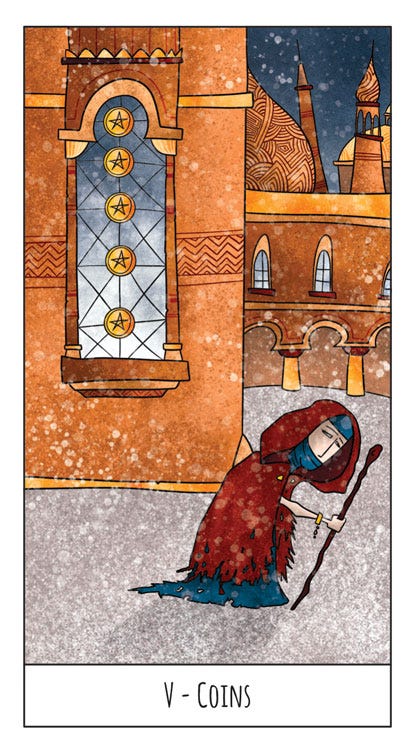

I wasn’t viewing the scene from afar, as we usually do, observing the two beggars limping past a stained-glass window. I was inside the building. I was the one behind the glass, the warm light flickering around me, witnessing their anguish from the comfort of sanctuary.

The Castle had shifted the perspective.

The shift was subtle, but profound. The card was reversed—not in the traditional divinatory sense, but in orientation. And by doing so, the Castle had altered its meaning. I wasn’t a neutral observer anymore. I was implicated. I was inside.

I wanted to scream, to open the window, to invite them in—but they turned and disappeared into the storm.

The Castle dismantles not only space and time but also meaning. Meaning here isn’t fixed; it unfolds in new directions, shaped by where you stand. And where you stand—inside or outside—can make all the difference.

This experience changed how I understand the Five of Coins. So often, we see the card as a symbol of our own despair, our isolation, our misfortune. We view it through the lens of the self. We fail to feel the cold the others walk through.

We look, but we do not see.

But the card holds a wisdom that asks more of us. It asks us to move beyond ourselves. It reminds us that sorrow, hardship, and loss are not private domains. They are part of a shared human tapestry.

To suffer is to be human. But to recognise another’s suffering, to let their grief echo in your own bones—this is the beginning of compassion.

The Five of Coins invites us to shift our gaze.

To move from isolation to empathy.

From self-pity to solidarity.

To stop seeing those lost in the snow as distant figures, and to understand: we are all sometimes outside the window, and we are all sometimes inside.

And perhaps, once we realise that, we might finally open the door.

Andrea

Is the reading then, some people don't have the empathy to let people who are cold and poor inside? When do you have agency as the reader to change things? You're inside the castle you could still open the doors if you have the empathy to do it.

I have seen this card as not realizing that help is there. Turn the corner - there's a door waiting for you to open. It's out of view and in our suffering sometimes we get lost and fail to see the help and hope that is available.