The Challenge of Definition: Lenormand, Tradition, and Innovation

Unearthing the Ghastly Lenormand Deck

When I first began sharing images of The Ghastly Lenormand From the Grave and conducted my initial readings with the deck, I was overwhelmed by the interest and curiosity it generated. I received a barrage of intriguing questions about the deck, all of which encouraged me deeply and, of course, warmed my heart. Every artist and author cherishes when their hard work is met with a positive reception from the public. There’s nothing unusual or extraordinary about that; it's something we all understand. However, amidst the flood of positive comments and feedback, I stumbled across a few remarks claiming that my deck was not a Lenormand deck at all, simply because I expanded it to 52 cards by adding extra ones.

At first, I found these comments rather odd. What caught my attention wasn’t the content of the criticism itself but the forceful manner in which it was expressed. The statements were made with such vehemence, as if they were absolute truths that everyone should accept without question. There was no room for dialogue, no opportunity for further discussion: The Ghastly Lenormand is not a Lenormand deck, period! There is nothing more frustrating than a statement presented—or, more accurately, aggressively pushed—as an absolute truth. I’ve always disliked this kind of attitude that excludes any possibility of doubt and arrogantly simplifies a situation, object, or person into rigid categories: This is X, that is Y, and that other thing is Z...

What triggered my deeper thoughts on this matter was the nature of the problem itself: the challenge of defining something. To assert that A does not belong to category X implies that you have a definition that determines which objects fall into category X and which do not.

This is one of the most intriguing problems philosophers have grappled with since the dawn of time, when we began to explore the world around us and our role in it as human beings. It may seem like a trivial or straightforward problem; after all, we all know how to recognize an object, situation, or entity and categorize it. A tree isn’t an animal, a rock isn’t a living being, and a chair isn’t a bed. It seems simple, doesn’t it? Well, that’s an illusion. There’s nothing more complex than solving the problem of definition.

I’d like to introduce you to the marvel of Theseus's Paradox, also commonly known as the Paradox of Theseus's Ship.

In Greek mythology, Theseus, the legendary king of Athens, rescued the children of Athens from King Minos after slaying the Minotaur and escaped on a ship bound for Delos. His ship was preserved as a precious relic from the day he returned, a day shrouded in the mists of time. Each year, the Athenians would commemorate Theseus's victory over the monstrous half-human, half-bull creature by taking the ship on a pilgrimage to Delos to honour Apollo. However, ancient philosophers soon began to turn their noses up and raised a simple yet profound question: After several hundred years of maintenance, during which many, if not all, parts of the Ship of Theseus were replaced one by one, was it still the same ship? Or, to put it differently, was it still Theseus's ship?

Plutarch preserved the account of this problem in his Life of Theseus:

"The ship wherein Theseus and the youth of Athens returned from Crete had thirty oars, and was preserved by the Athenians down even to the time of Demetrius Phalereus, for they took away the old planks as they decayed, putting in new and stronger timber in their places, insomuch that this ship became a standing example among the philosophers, for the logical question of things that grow; one side holding that the ship remained the same, and the other contending that it was not the same." — Plutarch, Life of Theseus 23.1

Over a millennium later, philosopher Thomas Hobbes ("Of Identity and Difference") extended the thought experiment by imagining that a ship’s custodian gathered up all the decayed parts of the ship as they were replaced by the Athenians and used those decaying planks to build a second ship. Hobbes posed the question: Which of the two resulting ships, the custodian's or the Athenians', was the same ship as the "original" ship? It’s a paradox—depending on your worldview, you might answer differently.

In contemporary philosophy, this thought experiment applies to the philosophical study of identity over time and has inspired various proposed solutions and concepts in the philosophy of mind, particularly concerning the persistence of personal identity… And this problem has profound implications for many aspects of our contemporary life.

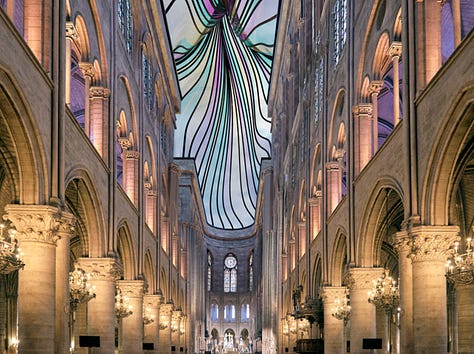

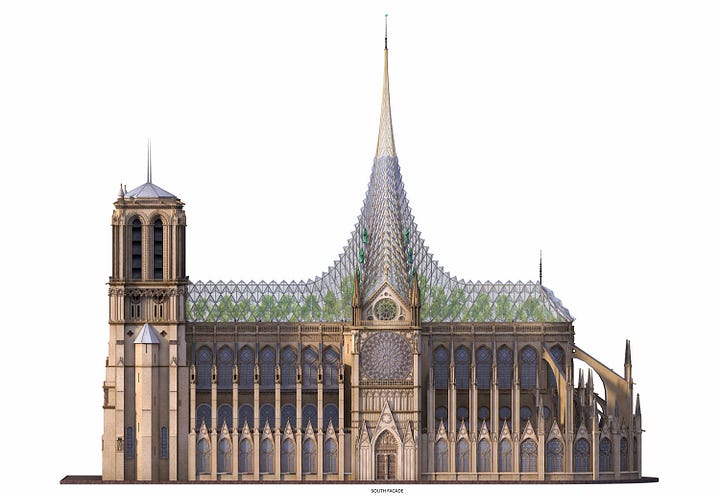

Consider the philosophical challenges we faced when rebuilding the roof of Notre Dame Cathedral after the devastating fire of 2019. Some architects argued that it was time for the cathedral to evolve, just as it had throughout its long history. They proposed modern structures, with futuristic designs that adapted the roof to a variety of unusual uses, including a roof garden, greenhouse, or even an artificial lake. On the other hand, many architects insisted that the cathedral should be restored to its original state, using the techniques, materials, and styles of the Middle Ages. This debate is a modern reflection of Theseus's Paradox. What the different schools of thought were really debating was the identity of the cathedral and the definition of one of the world's most iconic buildings. Ultimately, the decision was made to rebuild it as it was, respecting the history and image of Notre Dame as it stood before the fire.

History offers us fascinating examples of different answers to the same question. In much of Asia, ancient buildings have been restored in the same manner as the Athenians did with Theseus's ship—replacing damaged parts with new ones. What matters is the persistence of the exact shape, not the individual elements constituting it. Thus, you may see beautiful ancient pagodas and temples whose beams, stones, and decorations are... “new”. Are they still ancient buildings? It depends on how we perceive reality and how we choose to answer Theseus's Paradox.

If we walk through the labyrinthine palace of Knossos, with its rooms completely rebuilt and repainted by Evans, the archaeologist who discovered it, we may feel like we’re facing a fake—a sophisticated archaeological version of Disney World. For someone is acceptable, for other not. For someone is the “ancient palace” for other is not...

I’m merely skimming the surface of this complex problem, which has profound implications. We see the dramatic consequences of the paradox in the heated debates about defining gender: What defines a woman (or a man)? What makes a woman a woman? What are the necessary elements in defining what we agree to consider a woman? What about the aspects that fall outside the rules we set? Is it our genitals that define our sex? Our psychology and mind? Our chromosomes? Our genes? Our hormones? The ability to reproduce? Of course, I won’t answer these questions because they can’t be definitively answered. The complexity of the issue is such that our definitions may change depending on the context, and why not? Perhaps the rules for defining sex in the Olympics differ from those in common law or medicine. Reality is complex, intricate, and ever-changing, so perhaps our definitions should be as well.

Now, imagine the complexity of answering a moral question or trying to discern what is right or wrong, what constitutes art, and so on. The ramification of the Paradox of Theseus are...infinite!

Returning to the beginning, I am sure you can appreciate the philosophy behind that dogmatic assertion that The Ghastly Lenormand is not a Lenormand deck. What’s intriguing is not the statement itself, everyone is, of course, free to think what they think about it, but the possible mentality behind it—a mindset that views the world as a place where everything is perfectly ordered, definable, and defined, with no “borderlines” or ambiguities. It’s a dangerous vision of the world because limited and dogmatic, that deprives the world of its complexity and beauty. It may be practical because it’s not challenging. It’s safe. And this is precisely the perspective I wanted to challenge when I created the deck.

Of course The Ghastly Lenormand is not a “classical” Lenormand deck, because I added more cards -to capture aspects of our present time that the original traditional cards could never grasp, and how they could? Moreover, the deck can be read using Lenormand’s classical rules but is also open to new forms of spreads, offering a fresh dimension of reading and storytelling. This deck is inherently experimental. I wanted to use Lenormand’s semantics in different ways and see where they might lead the reader. Occultism, like everything else, evolves; it’s not merely the repetition of an unchanged, simplified formula. How often have we seen tarot cards reduced to a concept or two if we’re lucky? The complexity of a fascinating language that has evolved over centuries is completely lost—flattened into a few sentences.

I sincerely hope that The Ghastly Lenormand will challenge some ideas, prejudices, and biases that truly need to be reexamined. I will continue to share readings, experiments on how to use the deck, and connections between the cards and the cultural references that sustain their complexity—art, philosophy, history, and more. I hope that this little card game of mine can help shake the foundations of dogmatism and inspire others to break through its walls. The beauty of being alive lies in exploring, experimenting, toying with ideas and concepts, and growing through this fascinating process. Even my rules, ideas, and methods for using The Ghastly Lenormand are just one of many possibilities, and I wholeheartedly encourage you to challenge them, modify them, improve them, and give the cards meanings beyond my own. I am very curious about the way you will use the deck and your thoughts on the complex and fascinating issues we’ve explored in this article.

All the things I’ve written about us are untrue

they’re not what happened between us but what I wanted to see happen

those were my longings hanging from your unreachable branches

and my thirst pulled out of the well of my dreams

they were pictures I drew on beams of light.

Not all of what I wrote about us is true

Your beauty

that is to say a fruit basket or a picnic in the meadow

my being without you

that is my being the last streetlamp at the last corner of the city

the way I’m jealous of you

which means my running blindfolded among trains at night

my happiness

so to say the sun-drenched river which breaks its banks and overflows.

Whatever I’ve written about us is all lies

whatever I’ve written about us is all true.

-Nazim Hikmet-

Till the Next time

Andrea

Who were they? Let me at em! I’d tell them reality is absurd that they are absurd and that reality is defined by the observer. Besides 52 cards mean 36 Lenormand cards plus 16 extra New Lenormand cards. Bunch of dumb dumbs.

Those who strongly assert that the Ghastly Lenormand deck is NOT a true Lenormand deck do not understand the terms "evolve" or "evolution." It has opened the Lenormand structure to many new interpretations. We have many decks in the Tarot world that have extra cards that I feel add to working with the cards. I have never heard anyone denigrate these decks. There is room for everything, people!